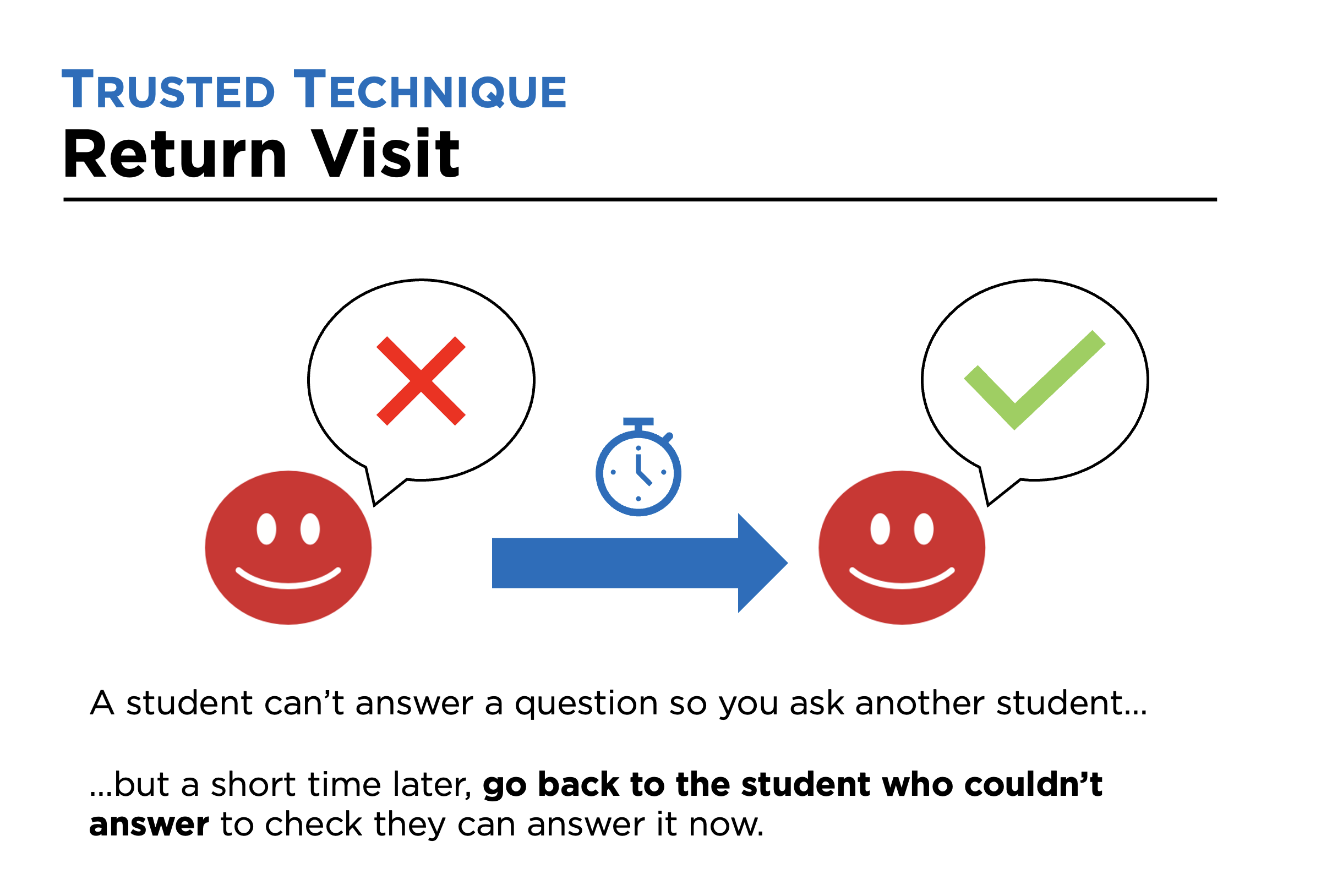

Return Visit

A student gets an answer wrong or says they don’t know, so you ask someone else, who answers correctly. A short time later, you go back to the student who didn’t know to ask them the same question (or one that is very similar). You make a Return Visit.

You could do this in different ways, including:

Asking the student the same question - or a very similar one - as part of whole-class teaching.

Asking everyone to answer the question on show-me boards, but paying particular attention to the student who didn’t know the answer or got it wrong previously. For example, you might say: ‘The last time I asked this question, not everyone got it right. So, I’d like to check that everyone knows now’.

Asking the student privately during supported or independent practice.

Why use this technique?

The reality of teaching is that students aren’t always going to know the answer to every question we ask. However, it is important that, ultimately, everyone does know. Return Visit helps to encourage students to pay attention and the teacher to check anything that wasn’t known previously is known now.

Example

In a science lesson…

Teacher: ‘Remind us what the three essential elements found in fertilisers are, please… Fraser.’

Fraser: ‘I don’t know.’

Teacher: ‘Okay. Well, one of them begins with N and the other two begin with P.’

Fraser: ‘I don’t know.’

Teacher: ‘Okay. Robbie, do you know?’

Robbie: ‘Nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus.’

Teacher: ‘Well done. Okay, so it’s important that everyone knows this because it’s knowledge we’ll keep referring back to in this topic. Just remind us what the three elements are, please, Fraser.’

Fraser: ‘Um… Nitrogen… Potassium… and, um… I don’t know.’

Teacher: ‘Well nitrogen and potassium are right. But we all need to know all three, and Robbie did just tell us. What was the other one, please… Nathan?’

Nathan: ‘Phosphorus.’

Teacher: ‘That’s right: phosphorus. Nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus are the three essential elements that we find in all fertilisers. I’m going to check everyone knows that using show-me boards in a few minutes’ time.’

Notes

Obviously, we aren’t trying to embarrass or humiliate any student with this technique. We are simply trying to help students learn the things they need to. If we didn’t care about their learning, we wouldn’t ask them again. But of course we do care, and that’s why it’s so important to make the Return Visit.

Whether you choose to tell students you will be coming back to them is a matter of professional judgement. If you’ve created a culture in which students know you are likely to do that, you shouldn’t need to tell them – they should be ready for it.

In the example, the teacher only left a few seconds before returning. However, it is sometimes better to leave it a bit longer to avoid a parrot-fashion response. If we do leave more time, it’s important that we remember to go back to the student again. Making a written note to do that can be helpful (so long as you remember to look back at the note!).

Another way to avoid parrot-fashion responses is to ask the student a slightly different question on our return. For example, if you ask a student to give an example of a metaphor and they say ‘I don’t know’, you could go to a different student and get a correct answer, and then go back to the original student and ask for a different example.

Complementary use of show-me boards

Return Visit can be powerful when used alongside show-me boards. For example, imagine a class have been asked to write a possible pH number for an alkali on show-me boards. Seeing that some of the class have got the answer wrong, the teacher addresses this. For example, they might ask a student who got the answer correct to explain why they chose the answer they did, or they might give feedback themselves, making clear which answers are correct and incorrect. However, with Return Visit, they wouldn’t leave it at that. Rather, at some point soon after, they would ask students the same or a very similar question, because they want to see evidence that all students can now answer this question correctly. For example, they might ask students to write a possible pH number for an alkali on show-me boards again, but everyone has to write a different number to the one they did last time (including students who had previously answered the question correctly).

Focused reflection

How well do you currently use this technique?

Is it a technique you will focus on developing?

If so, what are the key features you will focus on (things to do, and not do)?